Central Valley Aquifer of California supports 5 million residents and a $17 billion per year agricultural industry. More than 250 crops are grown in Central Valley, supplying up to half of the nation’s produce. It is truly the breadbasket of the country.

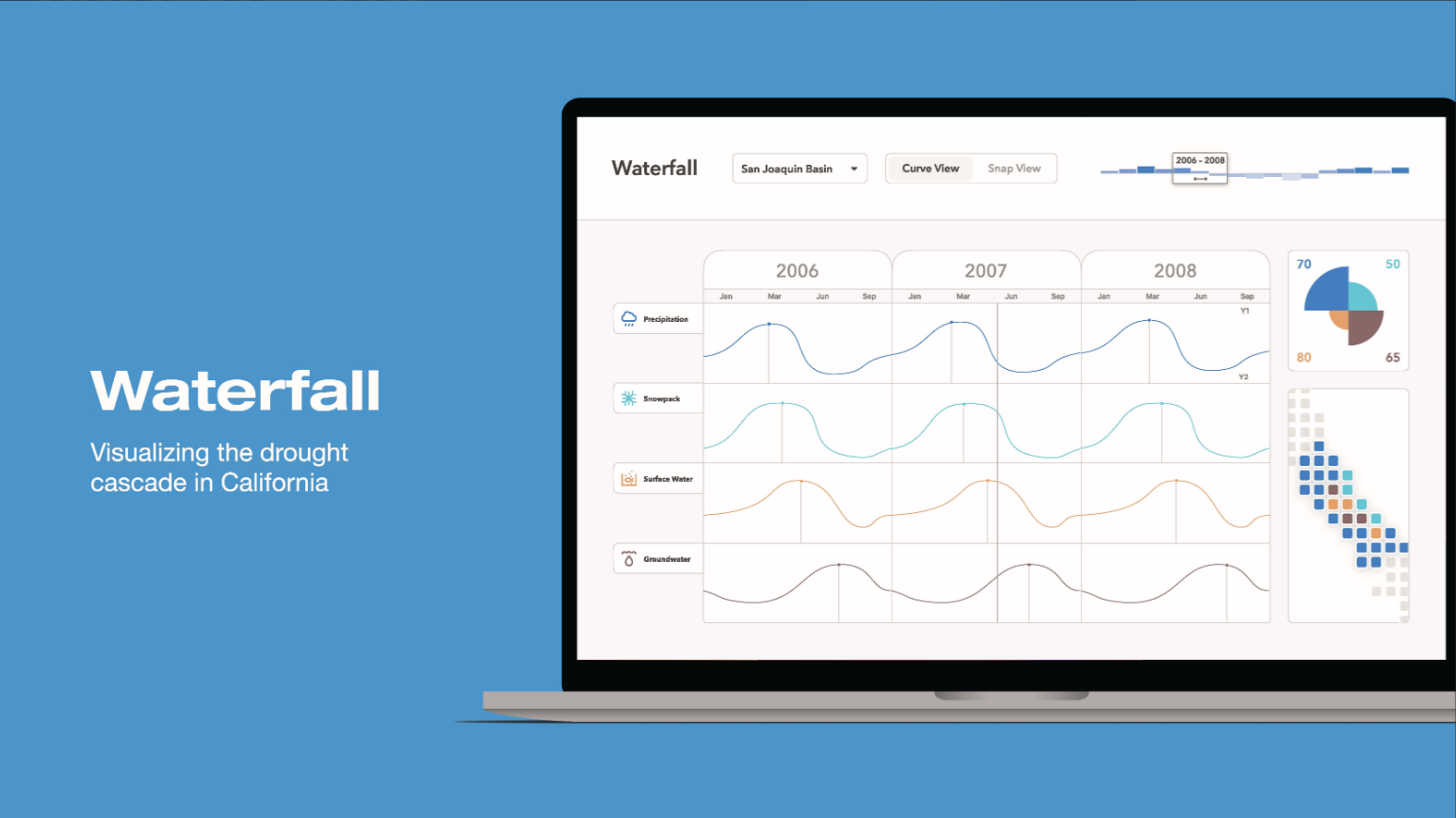

However, with high groundwater pumping, the valley is sinking.

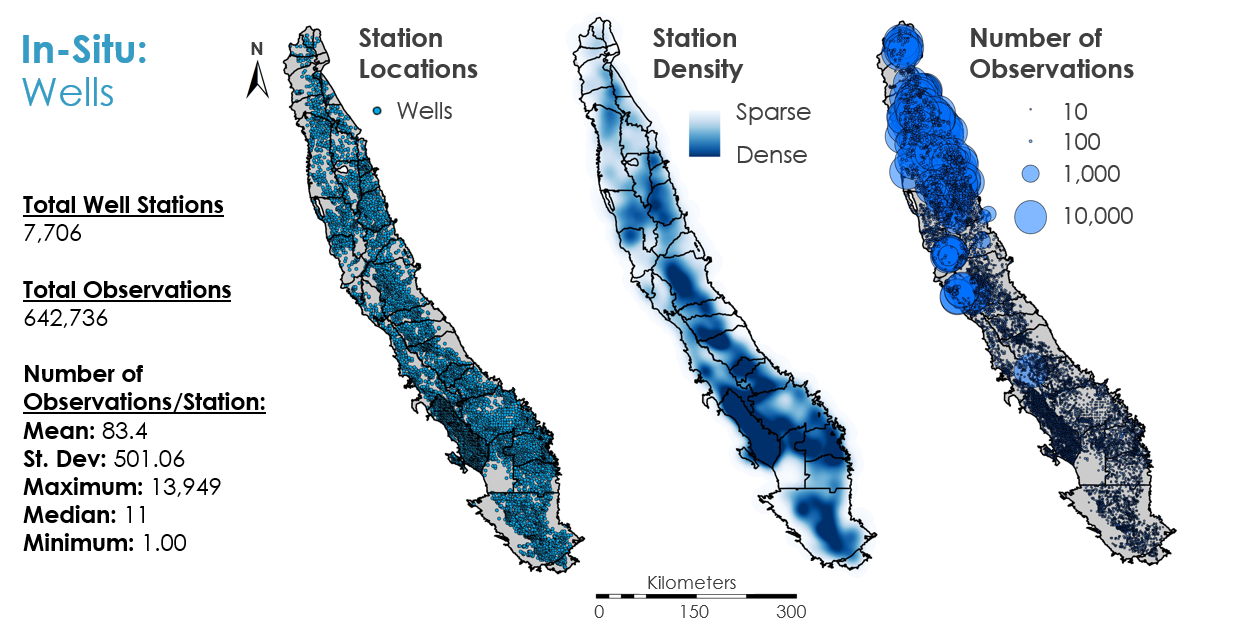

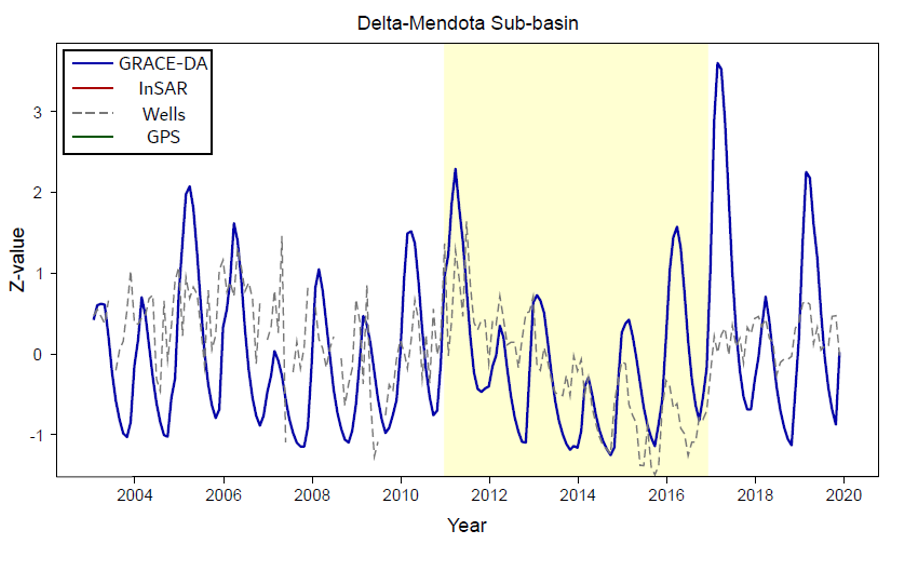

Well data can be sparse in space and time. We can use gravity-based missions like GRACE to track groundwater storage changes in the Central Valley.

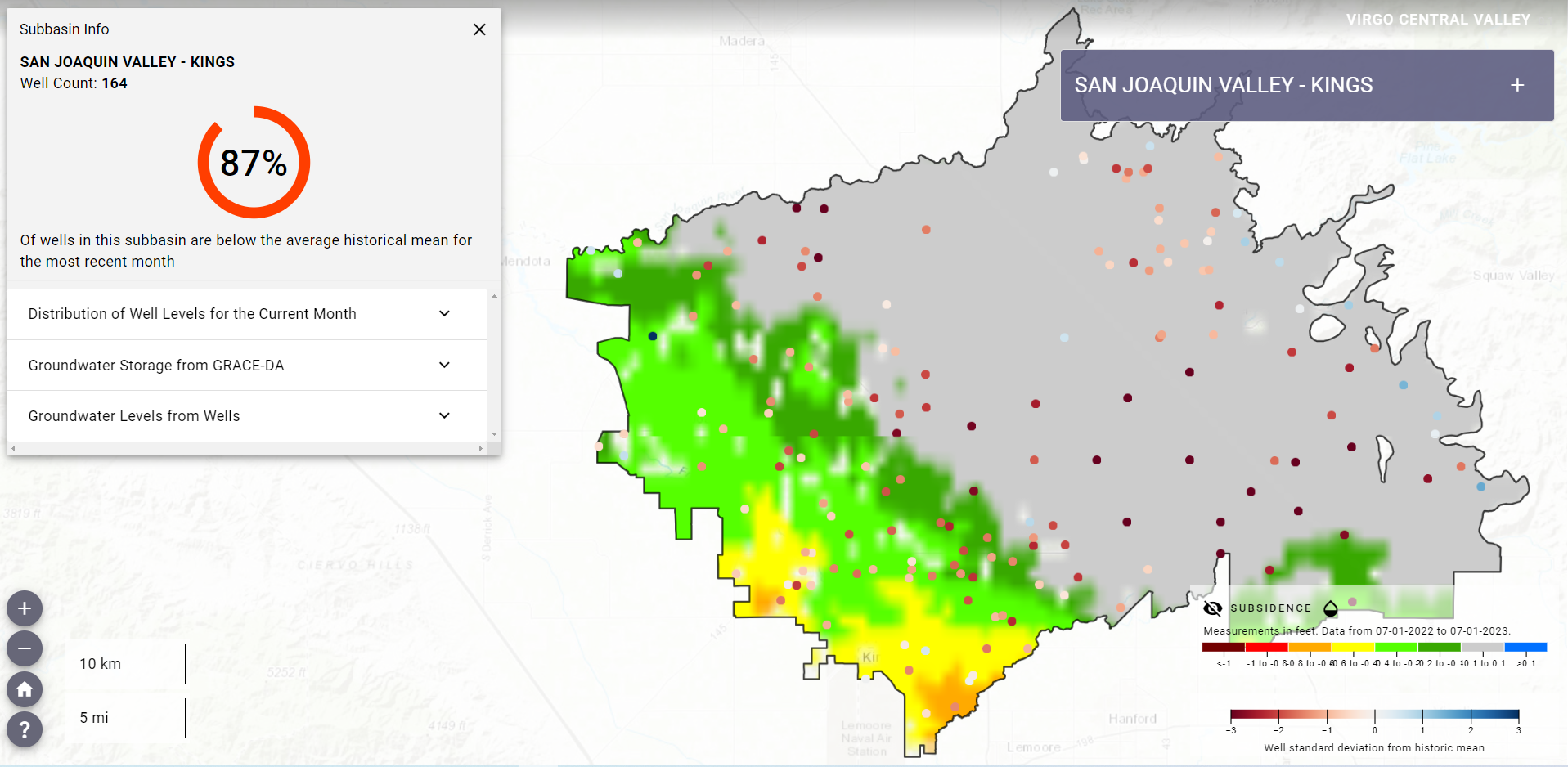

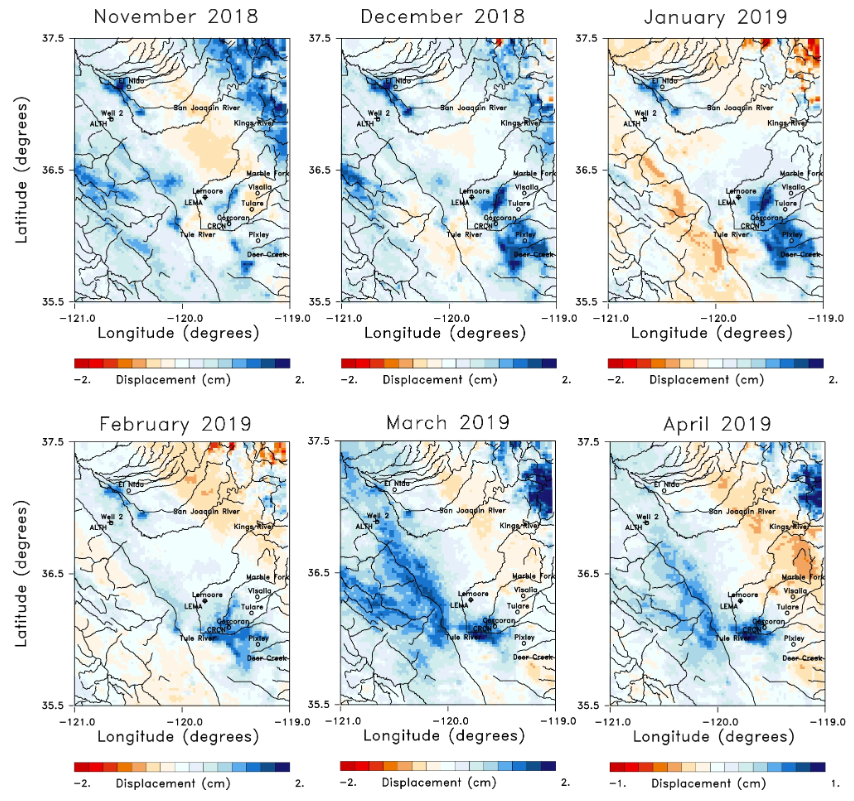

To track subsidence, radar methods such as InSAR can be used to understand land movement over time (figure below).

In my work with a team of NASA DEVELOP interns, we showed that remote sensing approaches can sufficiently complement or act in lieu of in-situ data.